by Elizabeth Minkel

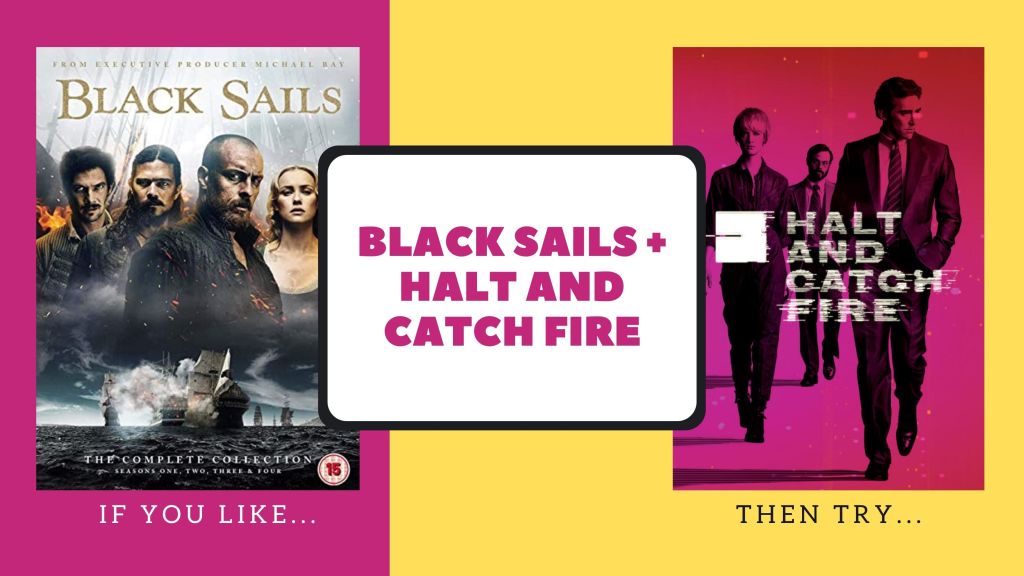

Given the open-ended prompt of “can you write and/or talk about greatest show of all time Black Sails”—an ask I’ve been lucky enough to receive a few times since I fell for the show and started evangelizing for it five years ago—it’s hard for me to pick just one area of focus.

If I don’t start by zeroing in on a specific character (Thomas Hamilton!), I usually jump first to Black Sails as a post-colonial text, refashioning the historical record as a political act, and centering the marginalized to reclaim those histories from their oppressors. But that leaves me wanting to talk about the broader themes of narrative manipulation, the meta-ness threaded throughout the show: characters in the story repeatedly talking about how they’re characters in a story, the way they deliberately play with the idea of “character” as they reinvent themselves.

Of course that then leaves me wanting to talk about pirates—narrative was what Golden Age piracy was all about! Real pirates didn’t actually do a ton of fighting: garner a fearsome enough reputation, and crews of the ships you’re raiding will surrender without spilling a drop of blood. But real pirate history just leads me to a wider history of the period, the actual rabbit hole I tumbled down when I was at the height of my Black Sails fandom: English history around the turn of the 18th century, imagining how the politics and social conditions of the late Restoration would have fundamentally shaped these characters’ lives.

But when this particular “can you write something about Black Sails” ask came in, I was falling hard for another show—one that, on its surface, doesn’t have very much to do with 18th-century pirates. AMC’s Halt and Catch Fire is a drama about technologists at the dawn of personal computing who are always on the cusp of the next big thing; it begins in Dallas, Texas in 1983, and follows the characters over the course of the next decade. Coincidentally, HACF aired at the same time as Black Sails—2014-2017—and also like Black Sails, its fourth and final season brought the story to an intentional (very satisfying!) conclusion.

Those are surfacey coincidences, of course. But digging a little deeper, parallel elements and themes run through them both: their ideas about reinvention, or the way they handle their protagonists’ queerness, or the way they show a broader spectrum of human relationships than a lot of media I’ve encountered, particularly the idea of partnership as romance. So when I was asked to write about Black Sails and half-joked, “As much as I love Black Sails, it’ll be hard for me to think about another show right now,” I was delighted when I was encouraged to actually write about them both: a letter of recommendation for HACF for people who love Black Sails.

Halt and Catch Fire was pitched as “Mad Men but computers in the 1980s,” and its first few episodes carry the clunkiness of that premise—the main characters are attempting to reverse-engineer an IBM PC, and critics were quick to draw on that conceptually as they accused the show’s writers of trying to reverse-engineer Mad Men, which was still on the air and was, of course, one of AMC’s biggest hits of all time. But halfway through the first season, it starts to shuck off that premise and free its characters from the archetypes that initially bound them—and by the second season, it starts to truly come into its own, shifting from a show about computers to a show about the people working on those computers.

Though it becomes a true ensemble show, the ostensible protagonist of HACF is Joe MacMillan, played by Lee Pace (if I wrote a “letter of recommendation for HACF for people who love Lee Pace,” it’d simply read, “Seriously you haven’t watched this yet??”). Joe is the aforementioned queer protagonist—he’s bisexual, written and portrayed in a beautifully nuanced way, especially with one particular storyline in the final season that’s my favorite of the entire show. A slick-talking salesman with grand visions for the future of technology, Joe initially brings together hardware engineer Gordon Clark (Scoot McNairy), a sort of sadsack failed-genius type, and software engineer Cameron Howe (Mackenzie Davis): a young, brash gamer who’s able to write such beautiful code that she never feels like she has to compromise on anything.

The early trio eventually breaks apart, and in the second season, Gordon’s wife, Donna (Kerry Bishé) is elevated from her season one role of “Gordon’s wife” to an equal fourth slot in the ensemble—also a hardware engineer, she enters into a working partnership with Cameron at an early online gaming start-up called Mutiny. Their partnership—and the enduring one between Gordon and Joe—are the heart of the show, even more than the characters’ configurations in traditional romantic relationships (in addition to the Clarks’ marriage, Joe and Cameron’s on-again, off-again relationship is a beautifully entertaining train wreck).

HACF leans into the theme of work-as-romance; it partly feels fueled by the technology industry itself and the mythos around start-up co-founders, but it’s partly about the specific way the show privileges the emotional depth of these working partnerships: what it means to love the person you’re collaborating with, and how the fracturing of a partnership can be as emotionally scarring as any romantic breakup. And because they’re all working around the same technologies and the same ideas, their romantic relationships complicate their work, too: it all leaves you beautifully frustrated by how much potential they could have, the things they could create, if only they could actually manage to work together.

Black Sails plays with similar configurations of overlapping platonic and romantic partnerships: where HACF leans into duos, Black Sails loves a trio, from Flint and the Hamiltons to Flint, Silver, and Madi, or the original Ranger trio followed by Max, Anne, and Jack. The murky spaces of these triangles offer some of the greatest pleasures of Black Sails: sorting out interpersonal desires from actual shared ideals and goals, and the sort of push-and-pull between them, as each side of the triangle brings traits that balance out the others.

The shows’ shared themes of reinvention feel both parallel to each other as well as contextually specific—where Black Sails plays with reinvention in its meta-exploration of narrative, HACF is working within the overarching ethos of the tech industry, where the cycle of failure, pivot, and reinvention are so elevated and romanticized that they’re essentially a Silicon Valley cliché. All the characters shift a great deal over the course of the decade-long timeline of the show, but none so much as Joe: there is a wholly new Joe MacMillan every season, each 180 a pleasure to try and untangle, as you sort the artifice from the genuine.

On the surface, these shows feel somewhat distant, audience-wise: my friends who love Black Sails tend to like genre fare, and my friends who love HACF like, well, other AMC dramas. But I think that the complexities of each of these shows—and the ways they overlap thematically—create plenty of space between the two. If you love Black Sails and you’re looking for a show that portrays a full and complicated array of intimacies between characters, I highly recommend Halt and Catch Fire. (Plus, a reminder: Lee Pace!)

Elizabeth Minkel (she/her) is a writer, editor, and consultant who focuses on digital technologies and fan culture. I’ve written about fandom (and other topics) for the New Statesman, The Millions, The Guardian, The New Yorker, and more. (See “clips” for a full(er) list.) I co-host a podcast about fandom called “Fansplaining” with Flourish Klink, and I collaborate with Gavia Baker-Whitelaw on “The Rec Center,” a weekly newsletter featuring fandom articles, fanart, and fic recs, which was a finalist for a Hugo Award in 2020.

Sign up for our queer nerdy newsletter!